It’s one of the undeniable, inescapable rites of the season: listening to “Frosty the Snowman.”

Short of barring yourself inside the walls of your own home and never venturing out for the entire month of December, you’re almost bound to hear the annoyingly cheerful lyrics and melody. In part because it’s a secular song, and therefore deemed somewhat less likely to offend or irritate listeners—an opinion held only by those who have either never heard the song or never listened to its lyrics.

It might help a little to realize that it’s also a fairy tale.

A fairy tale with outright murder in some versions, but we’ll get to that.

Songwriters Walter “Jack” Rollins and Steve Nelson did not, by most accounts, have murder in mind when they got together to write “Frosty the Snowman” in 1950. Or a hatred of the holiday season, to be fair. What they had in mind was money. A holiday song, they thought, might be just the thing, especially if they could get Gene Autry on board.

Singing cowboy Gene Autry had followed up his earlier 1947 Christmas hit “Here Comes Santa Claus (Right Down Santa Claus Lane)” with an even bigger hit, his 1949 recording of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (still one of the most popular recordings of all time of that song). and Rollins and Nelson had persuaded him to sing their “Here Comes Peter Cottontail.” If nowhere near as popular as “Rudolph” (only Bing Crosby was as popular as Rudolph), it was still a hit, and the songwriters figured that another holiday corroboration with Autry could also be a success.

Fortunately for all concerned, if less fortunately for the emotional stability of later holiday shoppers, Autry was looking for another seasonal song, and was willing to overlook that the melody sounded suspiciously similar to a popular 1932 song, “Let’s Have Another Cup of Coffee.” (YouTube has several recordings of this; I promise you that the lyrics are about coffee, pie, and Herbert Hoover, no matter how much it sounds as if the various singers are about to start singing about Frosty at various points.) Ignoring the numbers of people who would later complain about these similarities on YouTube, Audry released the first of many, many, many recordings of “Frosty the Snowman” in 1950, thereby unleashing snowman hell into the world.

By now, some of you may have simply tuned the words out, unable to bear them any longer. The rest of you can hum along to this plot summary: Frosty, a snowman, comes to life after an old silk hat is placed on his head. Realizing that he’s about to melt away in the heat, he decides to start running around, telling the children to run down the street after him—a street busy enough to require an active cop directing traffic. And then Frosty runs off, promising, in a threatening tone, to come back again some day. This is all followed by lots of thumpety thump thumps (some recordings omit this, though four year olds, in general, do not) and Frosty’s disappearance.

Alive? Dead? He was, after all, melting, and running around in the sun is one of those activities that tend to warm people up. I can’t be certain that magical snowmen have the same biology, but it seems likely. Which means that by chasing after him and encouraging that sort of thing, those kids are essentially participating in murder. The murder of a magically constructed creature, granted, which may not be considered murder, strictly speaking, in all fifty states (I am not an attorney) but, murder.

Not to mention that whole business with only pausing a moment when they heard a cop holler stop. Now, let us be completely fair here: I was not a witness to this event, and therefore speak with certainty about the cop’s motives. It’s possible that the cop just shouted “STOP!” because he figured that any talking snowman must be a recent escapee from a horror film and thus must be stopped at all costs. But, given that this cop is, as spelled out in the song, a traffic cop, it’s equally possible that he was trying to direct traffic, which means that Frosty only pausing for a moment and then continuing to run is the equivalent of running a red light or worse. Which is to say, even trying to put the kindest possible spin on this tale? Frosty is at best a minor criminal. At worst, he’s leading a group of small children through a busy intersection, completely ignoring the traffic signs.

Frosty is a menace, is what I’m saying.

(Though to be fair this is all slightly less concerning than the protagonists in “Winter Wonderland” who appear to think that a snowman can perform a valid marriage and will be happy to do so when he’s in town which IS NOW, protagonists. Are you expecting your snowman to get up and walk closer to the downtown area or return when you are finally ready to make things legal?)

To get back on topic, I’m actually less worried about Frosty, and more interested in the way the song uses the term “fairy tale.” Here, it’s meant less in the sense that I’ve been using it in these essays, and more in the sense of “lies, untruths, fiction”—something that adults believe isn’t real. I have argued here and elsewhere that if not exactly driven by data, most of the great fairy tales do present hard and real truths—which thus accounts for their survival. “Frosty the Snowman” is not one of the great fairy tales (I can’t even classify it as one of the great Christmas carols), but—nearly accidentally—it presents a similar truth. The children, the song says, know that the story is true, whatever the adults may say.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

More to the point, despite its dismissive use of the term “fairy tale,” the song does tell a fairy tale, in the grand tradition of a creature that should be inanimate coming to life—or at least, to conscious thought. It’s perhaps closest to “The Gingerbread Boy,” another tale of a vaguely human shaped figure coming to life and running—and eventually dying. “The Gingerbread Boy” is considerably less ambiguous than “Frosty the Snowman” in its original version, but it’s hard not to think that Rollins, Nelson and Autry didn’t have it, or similar tales in mind.

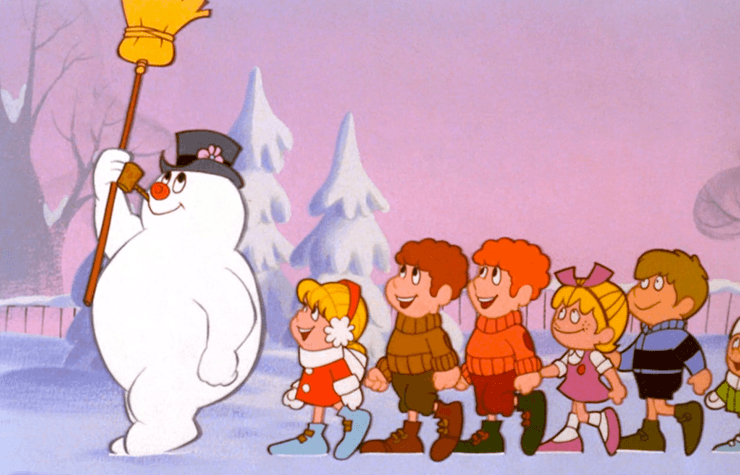

Whatever the inspiration (or outright plagiarism, in terms of parts of the melody) the song was another hit for Autry, popular enough to spawn a comic book and a Little Golden Book, and then, in 1954, into a three minute cartoon that slowly became a cult classic. But the song’s true fame would come in 1969, when Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass selected it as the basis for their next holiday feature. Aimed directly at children, it turned out to be even darker and considerably less law-abiding than the original song.

Rankin and Bass had founded Videocraft International just nine years earlier. Later better known as Rankin/Bass, the animation company endured years of reorganizations and name changes before finally mostly collapsing in 1989. In between, they became known—or infamous, depending upon your viewpoint—for two things: a remarkably steady output of cheaply made Christmas specials, many using stop motion animation, ranging from terrible to surprisingly okay, and remarkably cheap animated films and TV specials, some of which became cult classics in spite of—or perhaps because of—the animation issues. To save money, most of the Rankin/Bass animated films were produced in Japan. Rankin/Bass also made a few cheap and terrible live action films that went straight to television—the 1960s/1970s version of heading straight to video—but these, unlike their stop motion and other animated films, are largely forgotten today.

By 1969, Rankin/Bass was desperately searching for something to follow the success of the 1964 Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (which I have a number of complicated feelings about), the moderate failure of the 1967 The Cricket on the Hearth (which I have no feelings about), and the success of the 1968 The Little Drummer Boy (which I do not have complicated feelings about, largely because I cannot think of a single argument that can convince me that a drum solo is the most appropriate gift for a newborn). The two successes had both been based on Christmas songs; another holiday song, Rankin/Bass thought, might work.

But the studio faced an immediate problem: the story of “Frosty the Snowman” was even thinner than those of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” which had needed to add several characters and subplots to be stretched out to the required hour length—minus a few minutes for commercials. Then again, The Little Drummer Boy had been only a half hour. With a few more characters, “Frosty the Snowman” could be just stretched into a 25 minute cartoon. One that would be done with regular animation, not the stop motion animation the studio had usually used for its Christmas features, and which they would use again in later Christmas specials.

By “regular animation,” I mean “very cheap animation.” Frosty the Snowman was produced with extremely simple backgrounds, a limited number of animated characters in any given scene, many of whom get reused in later scenes, and virtually no special effects whatsoever. With no access to a multiplane camera, they could not use Disney’s well known (and relatively cheap) trick of filming cornflakes on a separate sheet of glass to create somewhat realistic looking “snow,” let alone create the effect of a moving camera—something cartoonists over at Warner Bros managed through manipulating background images. Frosty the Snowman does, well, none of this, and also contains several outright continuity mistakes, with Frosty sometimes having five fingers on a hand, and sometimes four. It’s bright and colorful, but that’s about all I can say about the animation.

The story opens with what the narrator claims is a magical snow that brings everyone together and makes them happy, which has not been which has not been my universal experience of snow, even the first snow of the season, but moving on. It also, conveniently enough, happens to be falling on Christmas Eve. A day where, for whatever reason, several kids are still in class, and—contrary to the supposed happiness effects from the snow—are not very happy. At all.

Perhaps recognizing this, their teacher has hired a magician called, somewhat improbably, Professor Hinkle, to entertain them. Unfortunately, Professor Hinkle is not very good at his job, and after losing his rabbit, he throws away his hat in irritation. The rabbit pops out and hops away with the hat. With the entertainment now at a clear loss, the kids are finally allowed to head out, build a snowman, and start singing the song. And the hat is finally able to land on Frosty’s head.

This all leads to various hijinks, including a trip to the North Pole, multiple attempts by Professor Hinkle to get his hat back, and—more recently—extreme concern from various Twitter users concerned that in nearly all of these scenes the kids are playing in the snow while wearing shorts, which, valid, especially after Karen, the only named kid, nearly freezes to death on three separate occasions, which would have been a lot less likely if you’d been wearing long underwear and snowpants, Karen.

I, on the other hand, was moderately concerned that the kids immediately decided that the only safe place for Frosty to stay, where nothing will ever melt, is the North Pole. And no, not because this all takes place prior to climate change becoming a significant concern: I’m questioning their geography lessons, though to be fair, I suppose that Frosty would need to travel through the generally warm equatorial regions in order to reach Antarctica, so, come to think of it, kudos, kids! That said, they also seem to be under the impression that you can take a train to the North Pole, so, let’s go back to focusing on those geography lessons, kids! Or maybe not, since it turns out that in this film, you can take a train to the North Pole, or at least pretty close to it, if you’re willing to jump on a number of different trains and pay a mere $3000 for the privilege.

Or maybe yes, since this entire train plot turns out to be mostly filler meant to try to stretch this film out to 25 minutes, with all of the characters except, I suppose, the train driver, jumping off the train well before reaching the North Pole. And then nearly freezing to death. It’s not really a good advertisement for trains, is what I’m saying.

Though I should note that Frosty, the rabbit, Karen, and the magician all board the train without paying for a ticket, like, yes, I get that you’re a kid, a talking snowman, a rabbit, and a failed magician, but this is still fare evasion, kids! It’s criminal! Just a misdemeanor in most cases, sure, but still!

This is hardly the only incident of criminal or near criminal behavior. Frosty the Snowman clarifies that, just as I thought, leading kids on a chase downtown right to a traffic stop does present a clear and present danger to people including people not on the street. And it all ends with the magician outright MURDERING FROSTY and TURNING FROSTY INTO A PUDDLE like, I was not in fact prepared for this.

I lied. It actually ends with Santa Claus agreeing that he might bring presents to the magician who just MURDERED FROSTY, however temporarily, though I guess we could see this as something he deserves as compensation for his loss of a magical hat, especially given that he does endure a punishment of sorts for this. About that punishment: I also kinda think that Santa should have ordered Professor Hinkle to do some sort of community service rather than just write the same sentence over and over, but, oh well.

I’m also not sure why Professor Hinkle wants Christmas presents more than a magical hat that he believes could turn him into a billionaire, a hat he was willing to commit murder for, but… deeply thoughtful this cartoon is not.

But the fairy tale elements are all here: a typically inanimate object coming to life through magical means, a quest for a magical location, not one but two characters falling into near “death,” brought back by magical means, and even a supernatural figure able to assist and give magical rewards and punishments.

And in its refusal to explain certain elements (why is the hat suddenly magical? why is there a hot greenhouse on the way to the North Pole?) it also fits smoothly into the fairy tale tradition, with its inclusion of the inexplicable. It’s not, as I said, one of the greatest of cartoons, or the greatest of the Christmas specials. But if you want to introduce a small child to the magic of fairy tales, and aren’t worried that the main lessons said child might learn from this film is that it’s perfectly okay to board trains without paying for a ticket and that if you do murder a snowman, the worst that might happen to you is the loss of future Christmas presents or needing to write multiple sentences over and over again….

Well. There’s a reason this cartoon keeps returning to television screens year after year.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.